Volodymyr Gubarkov

You might not need parameterized tests

March 2025

Let’s consider an example of a typical JUnit parameterized test:

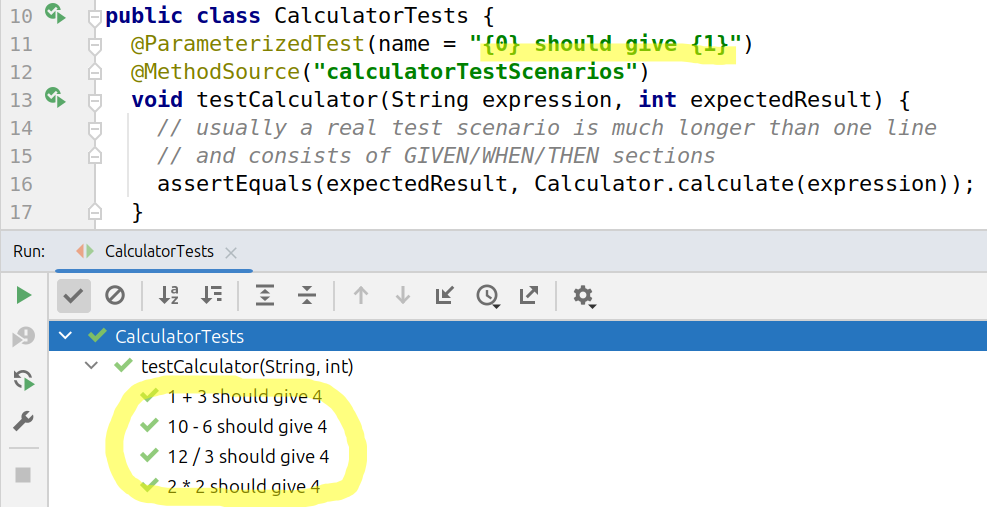

public class CalculatorTests {

@ParameterizedTest(name = "{0} should give {1}")

@MethodSource("calculatorTestScenarios")

void testCalculator(String expression, int expectedResult) {

// usually a real test scenario is much longer than one line

// and consists of GIVEN/WHEN/THEN sections

assertEquals(expectedResult, Calculator.calculate(expression));

}

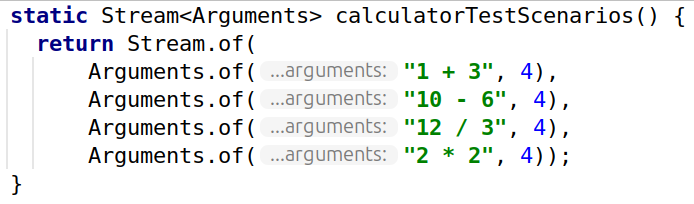

static Stream<Arguments> calculatorTestScenarios() {

return Stream.of(

Arguments.of("1 + 3", 4), // tests addition

Arguments.of("10 - 6", 4), // tests subtraction

Arguments.of("12 / 3", 4), // tests division

Arguments.of("2 * 2", 4) // tests multiplication

);

}

}

for a hypothetical application:

class Calculator {

public static int calculate(String expression) {

// actual implementation goes here

return 4;

}

}

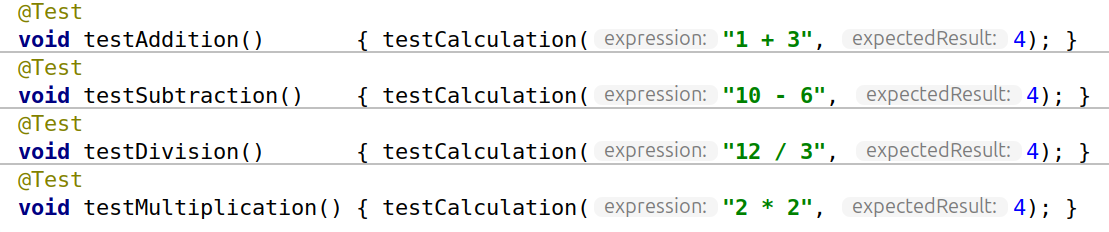

Conceptually the test above is almost identical to writing the tests without parameterization:

public class CalculatorTests {

void testCalculation(String expression, int expectedResult) {

// usually a real test scenario is much longer than one line

// and consists of GIVEN/WHEN/THEN sections

assertEquals(expectedResult, Calculator.calculate(expression));

}

@Test

void testAddition() { testCalculation("1 + 3", 4); }

@Test

void testSubtraction() { testCalculation("10 - 6", 4); }

@Test

void testDivision() { testCalculation("12 / 3", 4); }

@Test

void testMultiplication() { testCalculation("2 * 2", 4); }

}

Surprisingly, the less-clever second variant also has some advantages:

-

It’s conceptually simpler, less framework magic involved (of JUnit test engine).

-

With parameterized testing, running a specific test case becomes somewhat cumbersome.

-

You are able to apply meaningful names to each of separate

@Tests. If needed, you are able to also add javadocs to some/all of them to clarify each test scenario (example: reference to a business requirement, etc.). -

It’s more IDE-friendly (therefore, maintainable, comprehensible).

Compare this (notice, how IDE helps with the meaning of arguments):

to this (not much help):

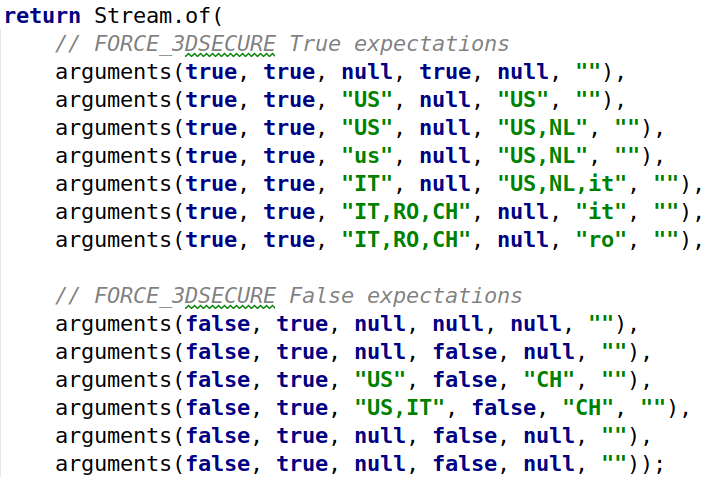

If this is not convincing enough, here is an example from a real project:

☝ Good luck matching to test parameters!

To be fair, there is at least one argument in favor of parameterized tests: you can use test names parameterization to get human-readable names:

However, I think this is only usable if the test has up to a few parameters.

Conclusion

There is nothing wrong in not using parameterized tests and preferring less-clever ordinary tests approach.

It’s also worth mentioning how in other case using the same strategy of preferring “ordinary” tests over “clever” tests helped speed up the test suit.

If you noticed a typo or have other feedback, please email me at xonixx@gmail.com